The past few years have been hard on most of us, and there is no sign of things getting any better in the near future. Handling stress has never been as challenging, or as vital. This is why I would like to take a moment to share an updated model of stress, and a few simple strategies for managing your response to stress.

In 1915, while studying the sympathetic nervous system and its response to stress, Walter Bradford Cannon coined the term “Fight or Flight”. This was later amended to Fight, Flight or Freeze. Based on subsequent observations, several new terms were added, like Fawn, Faint, and Flop. For simplicity’s sake many therapists just refer to a state of hyper-arousal or the Acute Stress Response.

The role of the sympathetic nervous system in stressful situations (fight/flight) is well understood. However, the role of the parasympathetic, and in particular, the vagus nerve has long been misunderstood.

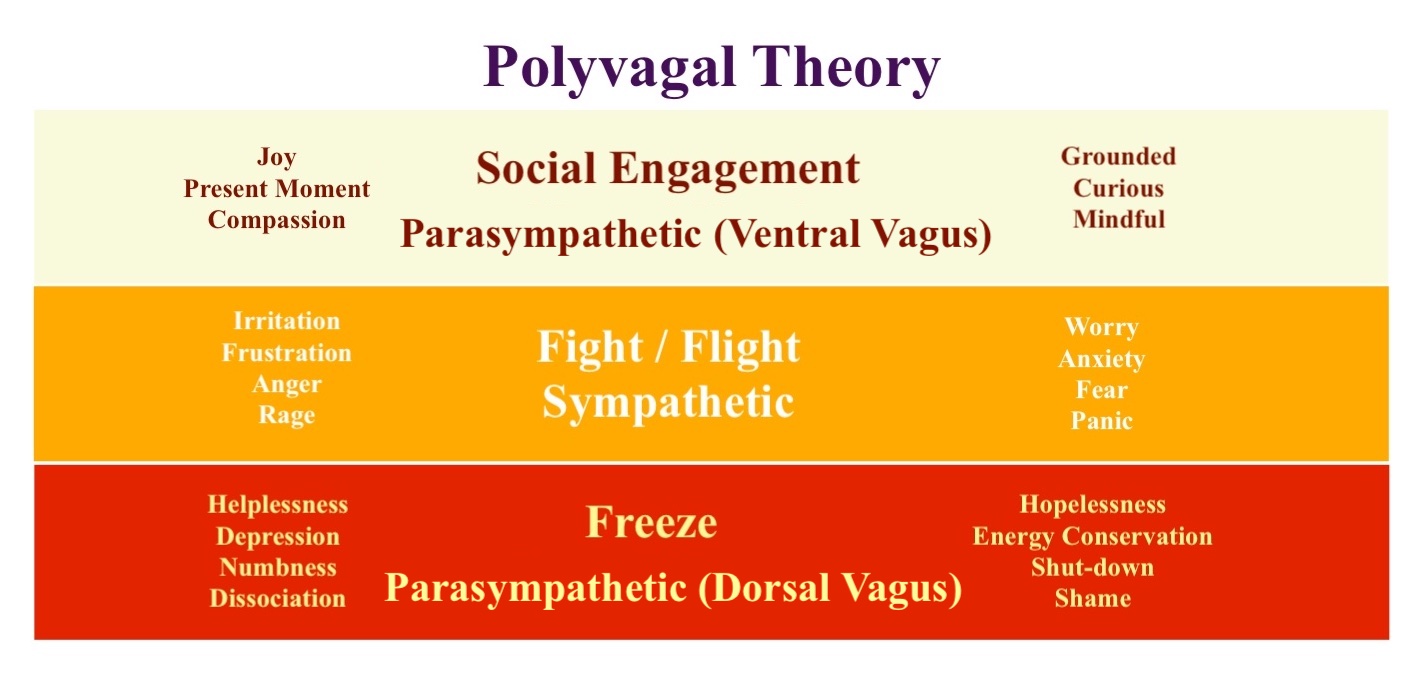

In 1994 Stephen Porges shared a new model which he calls the Polyvagal theory, which is steadily gaining support among therapists, including yoga therapists. Porges’ insight was that the two primary branches of the vagus nerve, the dorsal branch and ventral branch originate from different locations in the brain and spinal cord, follow different pathways through the body, and have very different effects on the body. In short, they are better thought of as two separate and different nerves, despite being called ‘branches’ of the vagus nerve.

The so-called dorsal branch of the vagus nerve is what gives rise to the freeze response, along with feinting, fawning and flopping. By contrast, the ventral branch of the vagus nerve is associated with higher levels of social engagement. It also has the capacity to moderate the effects of the fight/flight/freeze response.

The so-called dorsal branch of the vagus nerve is what gives rise to the freeze response, along with feinting, fawning and flopping. By contrast, the ventral branch of the vagus nerve is associated with higher levels of social engagement. It also has the capacity to moderate the effects of the fight/flight/freeze response.When the ventral branch of the vagus nerve is active, it converts the fear-basedFreeze Response into what Herbert Benson called the Relaxation Response (ex. chimpanzees grooming each other and napping). Likewise, when the ventral vagus is active it converts the fear-based Fight/Flight response into playfulness and adventure (excitement without fear).

In short, when the ventral vagus nerve is active, we are more compassionate, joyful, grounded, and present. And when the ventral vagus nerve shuts down, we respond to stress with fear, resulting in some variation of a fight/flight/freeze/fawn/feint/flop response.

In short, when the ventral vagus nerve is active, we are more compassionate, joyful, grounded, and present. And when the ventral vagus nerve shuts down, we respond to stress with fear, resulting in some variation of a fight/flight/freeze/fawn/feint/flop response.

So how can we activate our ventral vagus nerve?

There are several techniques that can activate the ventral vagus, including specific chiropractic adjustments, massage, meditation, and eye exercises… but by far the simplest, and for many the most effective, is simply to yawn a few times and then practice breathing slowly with the diaphragm.

One spectacular yawn or several mediocre yawns can reset the ventral vagus nerve. Yawning releases oxytocin, nitric oxide, opiate derivatives, and a host of other neuro-transmitters associated with relaxed social engagement.

Imagine a pride of lions, napping in the heat of the afternoon, yawning and grooming themselves and each other without a care in the world.